By eight years after high school graduation, students who just barely won admission to a four-year college see an earnings premium and ultimately more than offset their college costs.

Attending a four-year college eventually results in higher earnings, even for "marginal" students whose high school records do not guarantee admission. In Marginal Returns to Public Universities (NBER Working Paper 32296), Jack Mountjoy studies the post-college earnings of students in Texas who are on the margin of being admitted, based on their standardized test scores, to state universities.

This research provides new evidence on the long-standing question of whether college-bound students are inherently distinct from those who do not attend college, which would make it difficult to attribute later-career earnings disparities to college attendance. By looking at students whose SAT or ACT scores were only slightly above an arbitrary cutoff line, Mountjoy argues, he is studying "marginally admitted" students who are not meaningfully different from rejected students with scores just below the cutoff. Indeed, Mountjoy shows that observable measures of students' academic preparation and family background are well-balanced across the cutoff, with only the likelihood of admission jumping discontinuously.

Mountjoy chose to study Texas because of its high-quality administrative data and its large size: Texas public universities enroll 10 percent of all public university students in the US. He analyzed all applicants to these universities between 2004 and 2016 and identified two groups of "marginally admitted" students. Students in one group were admitted to at least one other Texas public university, and thus had another (typically less selective) four-year college option to fall back on if rejected. Students in the second group had no such option and mostly fell back to a two-year community college if rejected; they saw much larger benefits of four-year college admission than students in the first group.

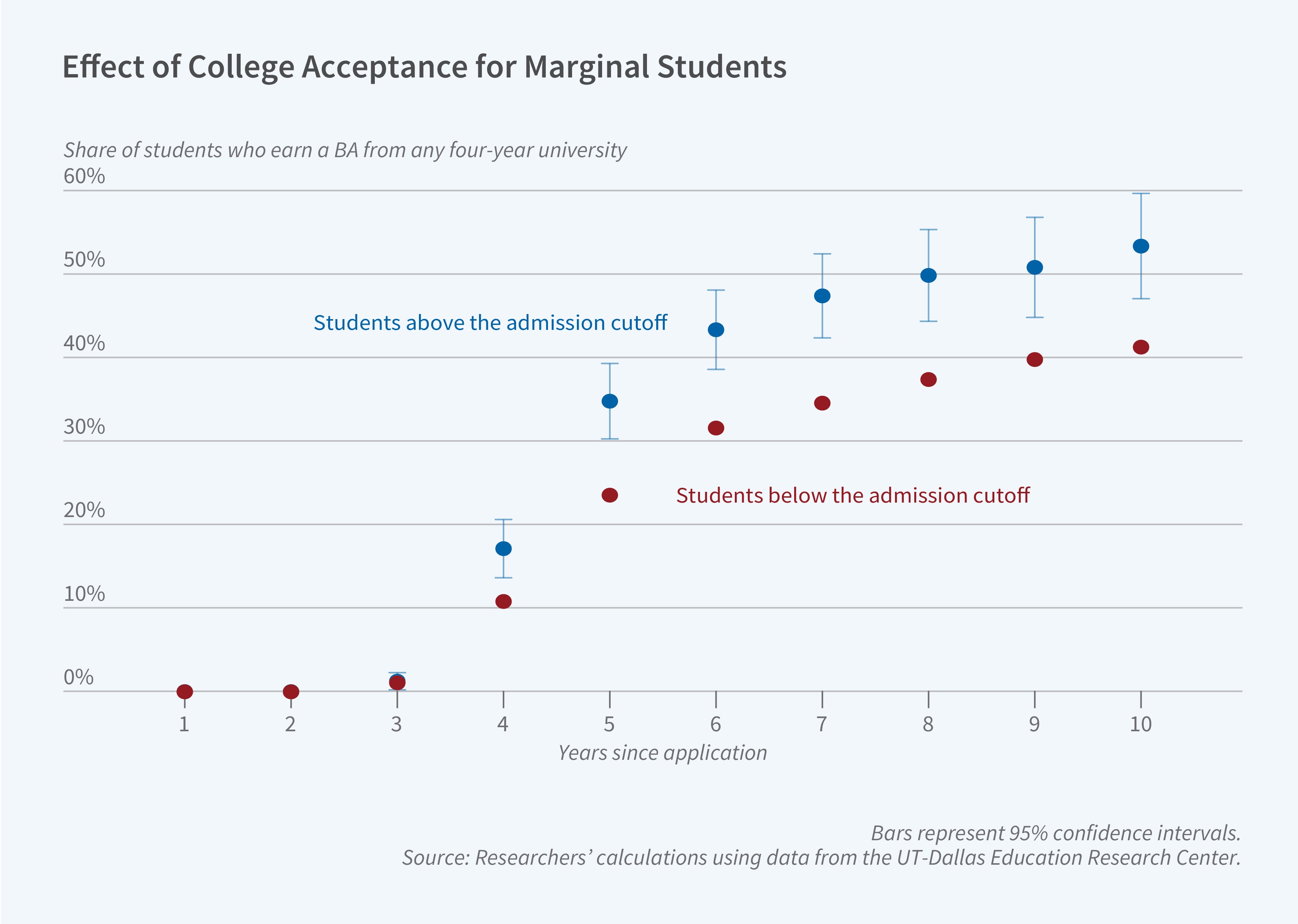

The data show that marginally admitted students attend colleges with peers who had better high school test scores, who were less likely to have received free or reduced-price lunch in high school, who have a higher six-year bachelor's degree completion rate, and who have higher post-college earnings. Marginally admitted students themselves become 12 percentage points more likely to earn a bachelor's degree than students whose standardized test scores were just below the admissions cutoff score.

Marginally admitted students attend schools with higher posted tuition costs, but these costs are largely offset by increased grant aid. These students take out about $5,000 more in loans to finance additional consumption costs, such as room and board, relative to their barely rejected counterparts.

In the first four years after high school, marginally admitted students earn less than their peers whose scores were just below the acceptance line, in large part because they are more likely to be enrolled full time in higher education. They do not see an earnings premium in years 5 to 7 after finishing high school, but starting in the eighth year, their average earnings are 5 to 10 percent greater than those of their barely rejected peers. Taxpayers, who subsidize the majority of this additional education, eventually reap a return as well: after 25 years, the increased tax revenue from marginal students' higher earnings surpasses the costs of attending college.

— Greta Gaffin

No comments:

Post a Comment