Identifying effective teachers and principals and providing financial incentives for them to work in lagging schools raises achievement test scores in math and reading.

Over the last decade, the Dallas Independent School District (ISD) has dramatically changed how it sets salaries. Jettisoning a typical pay scale tied to years of experience and academic credentials, Dallas began compensating educators based on a rigorous evaluation system. The result, according to two recent, related studies, is a marked improvement in student achievement.

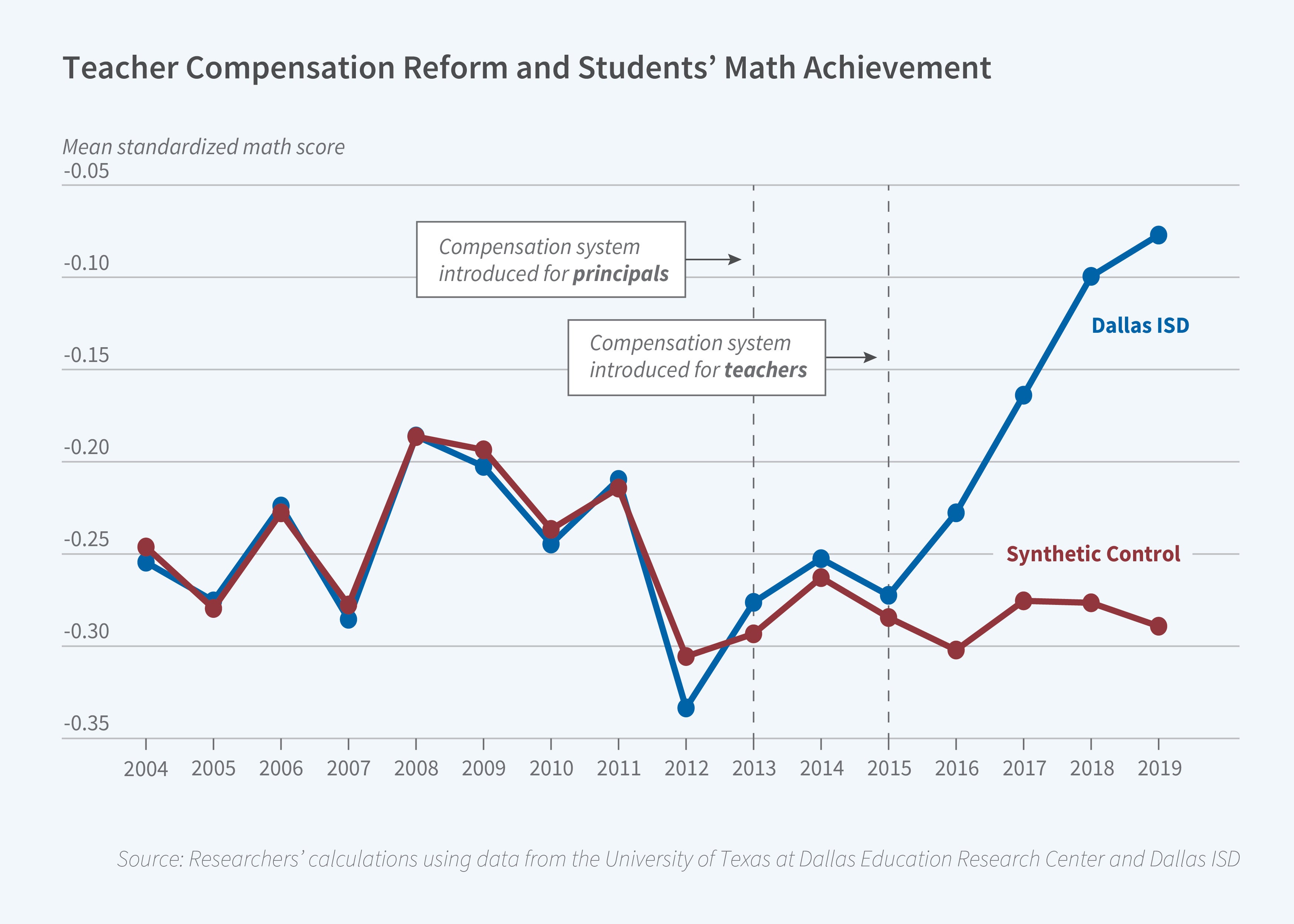

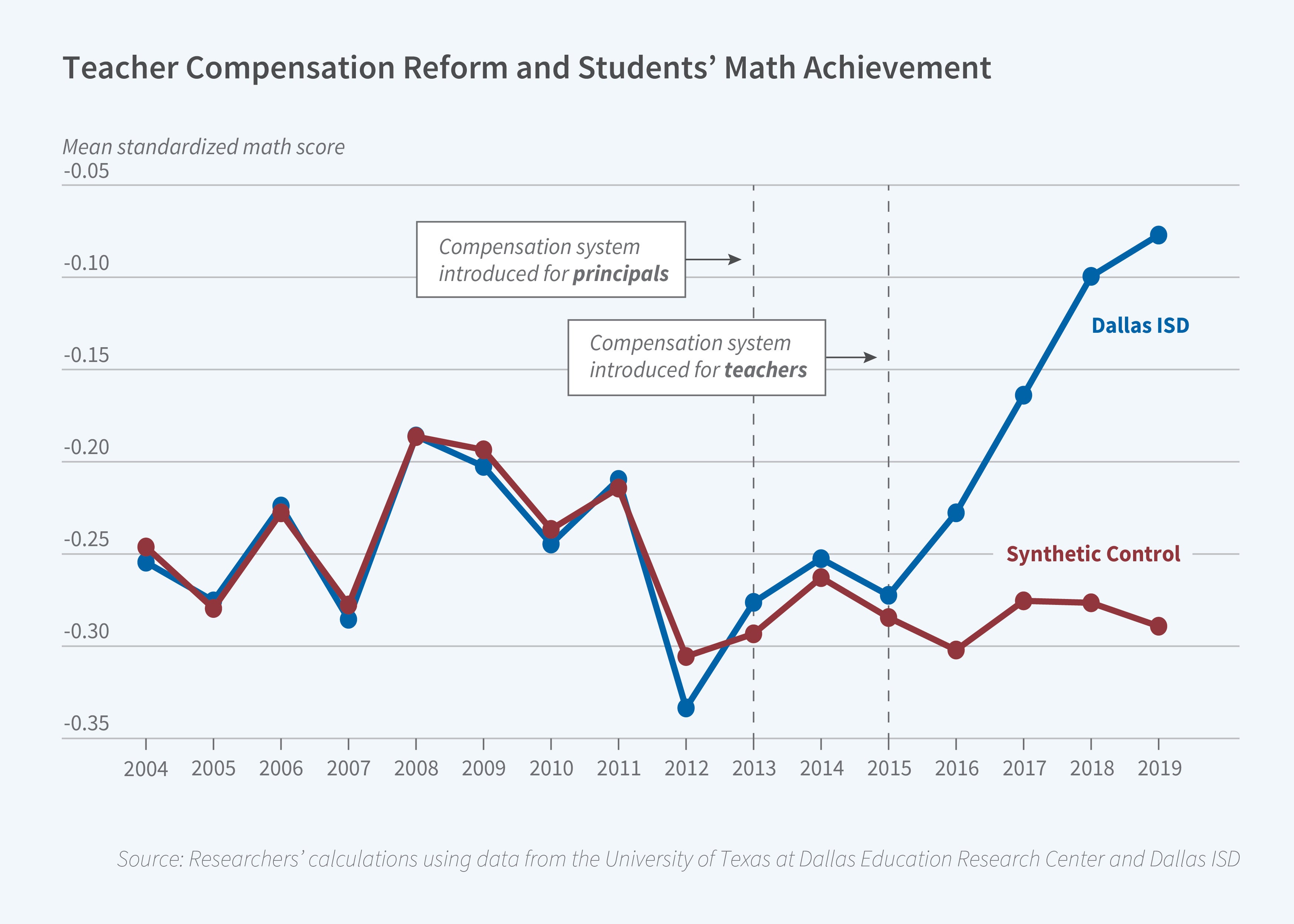

In The Effects of Comprehensive Educator Evaluation and Pay Reform on Achievement (NBER Working Paper 31073), Eric A. Hanushek, Jin Luo, Andrew J. Morgan, Minh Nguyen, Ben Ost, Steven G. Rivkin, and Ayman Shakeel show that the new system increased the achievement levels of Dallas students above those of students enrolled in comparable schools with traditional pa y scales elsewhere in Texas.  Under the Principal Excellence Initiative, introduced in 2013, and the Teacher Excellence Initiative, which followed two years later, the Dallas ISD pays educators based on their contributions to student achievement, supervisor observations, student or family feedback, and, in the case of principals, efforts to support teacher improvement. As an incentive to focus on disadvantaged students, principals are also judged on progress in reducing achievement gaps between their students and the district mean. Based on aggregate evaluation scores, educators are sorted into rating bins that are the primary factor in setting their salaries.

As their main control group, the researchers used schools drawn from the 20 largest Texas districts with at least 60 percent low-income students. The impact of the Dallas reforms became clear in 2016 when, after an initial period of high teacher turnover, math and to a lesser extent reading achievement scores rose. Prior to introduction of the new salary scheme, scores in both the Dallas schools and the control group, which serve large shares of disadvantaged students, were substantially below the statewide mean; afterward, the students in Dallas rose to nearly the state mean level, while the control group did not improve.

Though initially disruptive, the teacher turnover resulted in a stronger staff, as teachers who left the system on average had lower evaluation scores than those who remained. The analysis attributes 15 percent of the improvement in math achievement to changes in the composition of the teaching staff. Other key contributing factors included higher incentives, enhanced teacher support, and stronger school leadership.

In Attracting and Retaining Highly Effective Educators in Hard-To-Staff Schools (NBER Working Paper 31051), Morgan, Nguyen, Hanushek, Ost, and Rivkin report that Dallas obtained immediate and sustained improvements in student achievement in its lowest-ranked schools by using the new evaluation system to identify talented teachers and reward them with stipends if they worked at those schools.

The program selected the worst performing schools based on test scores from 2014, two years before it was implemented. The researchers used as a control group the next-lowest-performing schools in Dallas, a group exposed to similar conditions in the run-up to the program's implementation.

Overall, the program raised average achievement at the lowest-performing schools nearly to the districtwide average. Math scores saw greater gains, but reading increases were substantial as well. Students who attended targeted schools for two or more years continued to show large increases in achievement in middle school, suggesting lasting improvements in cognitive skills. The second wave of students showed similar results to those in the first, demonstrating that the program could be scaled up.

Ironically, the rewards system's success resulted in its undoing. When achievement scores at the targeted schools in the first wave approached the district average, stipends were largely removed. Consequently, the researchers write, "turnover jumped among the most effective teachers and test scores fell substantially."

— Steve Maas

|

Mergers in Consumer Packaged Goods and Consumer Prices

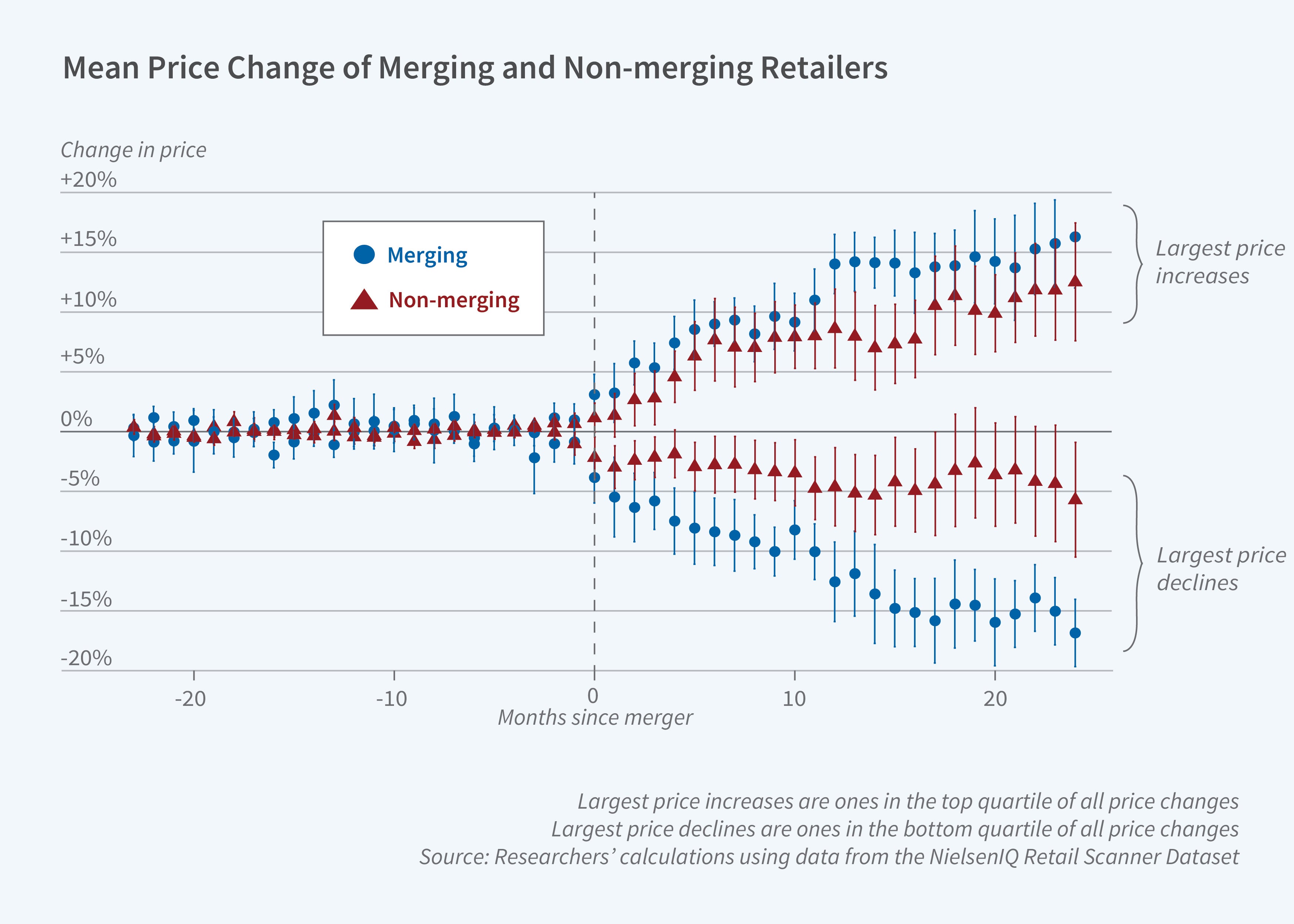

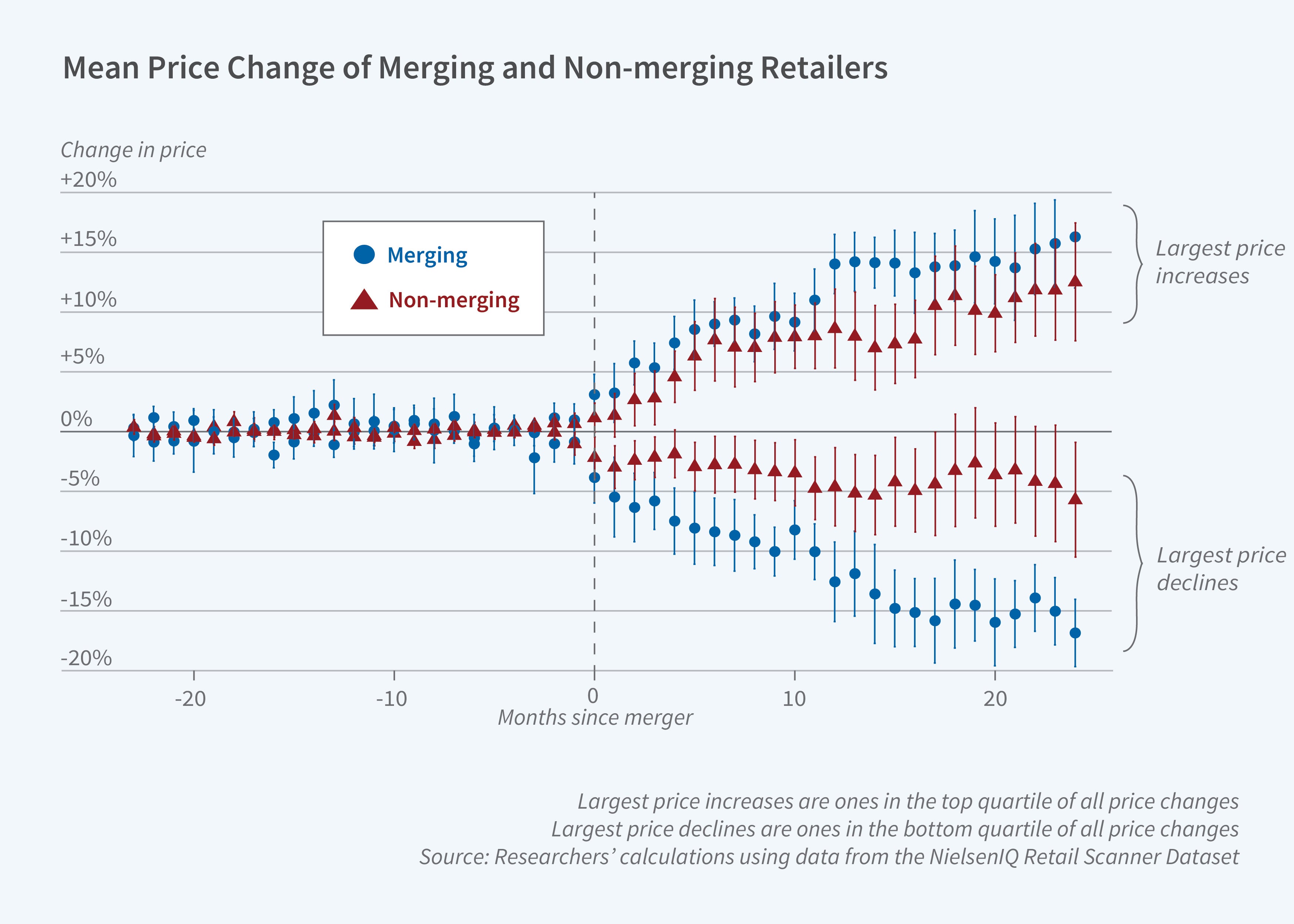

Consumer packaged goods producer mergers led to disparate price changes. One-quarter resulted in price drops of 2.3 percent or more, while another quarter led to increases of at least 5.3 percent. Mergers can increase prices if the merging parties gain market power due to the deal. They can decrease prices if the union induces cost savings that the firms pass through to consumers. The regulatory agencies that review mergers must determine which scenario is more likely.

In Merger Effects and Antitrust Enforcement: Evidence from US Retail (NBER Working Paper 31123), Vivek Bhattacharya, Gastón Illanes, and David Stillerman study the results of 50 mergers. The deals examined were valued at $280 million or more and involved producers of consumer packaged goods sold at grocery stores and mass merchandisers. These producers sell many products; these mergers impacted 126 product markets.  The researchers study the effect of mergers on the sale prices and quantities sold of individual products in the two years before and after completed mergers, both for the merging parties and for competitors. They rely on data from the NielsenIQ Retail Scanner Dataset.

After a merger, the average price of a product sold by the merging parties decreased by 0.1 percent. Over the same period, prices for products sold by nonmerging firms rose by 2.1 percent. These averages mask substantial differences across mergers, consistent with the notion that some deals lead to stronger exertion of market power while others lead to cost synergies. In 25 percent of the analyzed mergers, prices fell by at least 2.3 percent. Another 25 percent led to price increases of 5.3 percent or more.

Aggregate quantities decreased by 2.3 percent on average after a merger, again with substantial variation: the first quartile saw a drop of 6.9 percent, compared with an increase of 3.1 percent for the third quartile. Significant quantity declines following a merger correlate with narrower distribution networks and with reductions in product portfolios.

The researchers apply their findings to estimate the decision rule that agencies used in deciding whether to challenge proposed mergers. They find that during their study period, 2006 to 2017, US antitrust agencies challenged mergers with an expected sales-weighted average price increase of more than 8.6 percent. Reducing the challenge threshold to 5 percent would have blocked few procompetitive mergers while reducing the probability of approval for anticompetitive mergers. However, it would have tripled the number of proposed mergers that the agencies would have had to challenge. — Linda Gorma |

No comments:

Post a Comment