Students who participated in STEM summer programs at a major US university were more likely to remain enrolled in college through their senior year than students in a control group.

Governments and many private organizations have invested in programs to support diversity in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) pipeline, including summer programs for high school students. There is little rigorous evidence of the efficacy of these programs, however. In STEM Summer Programs for Underrepresented Youth Increase STEM Degrees (NBER Working Paper 30227), Sarah R. Cohodes, Helen Ho, and Silvia C. Robles find that students offered seats in STEM summer programs are more likely to enroll in and graduate from college.

The researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial of a suite of summer programs aimed at increasing the number of underrepresented students pursuing STEM degrees and careers. They collected information on students from their program application through college graduation, with or without a STEM degree. In the summers of 2014, 2015, and 2016, cohorts of high-achieving, STEM-interested students were randomized into one of four groups, three STEM-focused programs plus a control group. The programs were held in the summer between the junior and senior years of high school. The programs were held at an elite technical university in the Northeast. They differed in their modality and intensity: six weeks full-time on-site, one week full-time on-site, or six months with periodic meetings online. Students were selected into the randomization pool based on their academic preparation as well as a holistic assessment of need that included whether they had backgrounds that were underrepresented in STEM fields.  Participation in all three programs increased the likelihood of application to, acceptance at, and enrollment in the host university, with the largest magnitudes coming from the six-week program. Eighty-seven percent of students in the control group attended a four-year college immediately after high school graduation, and the programs increased this by 2 to 4 percentage points. However, by the fourth year of college, enrollment among the control group dropped to 75 percent, most likely reflecting students dropping out of college or taking time off before completion. In contrast, those offered a seat in any one of the three STEM summer programs were 3 to 12 percentage points more likely to still be enrolled in a four-year college after four years. The STEM summer programs also increased enrollment at Barron's magazine's most competitive colleges, and the likelihood of application to, acceptance at, and enrollment in the host institution for the STEM programs.

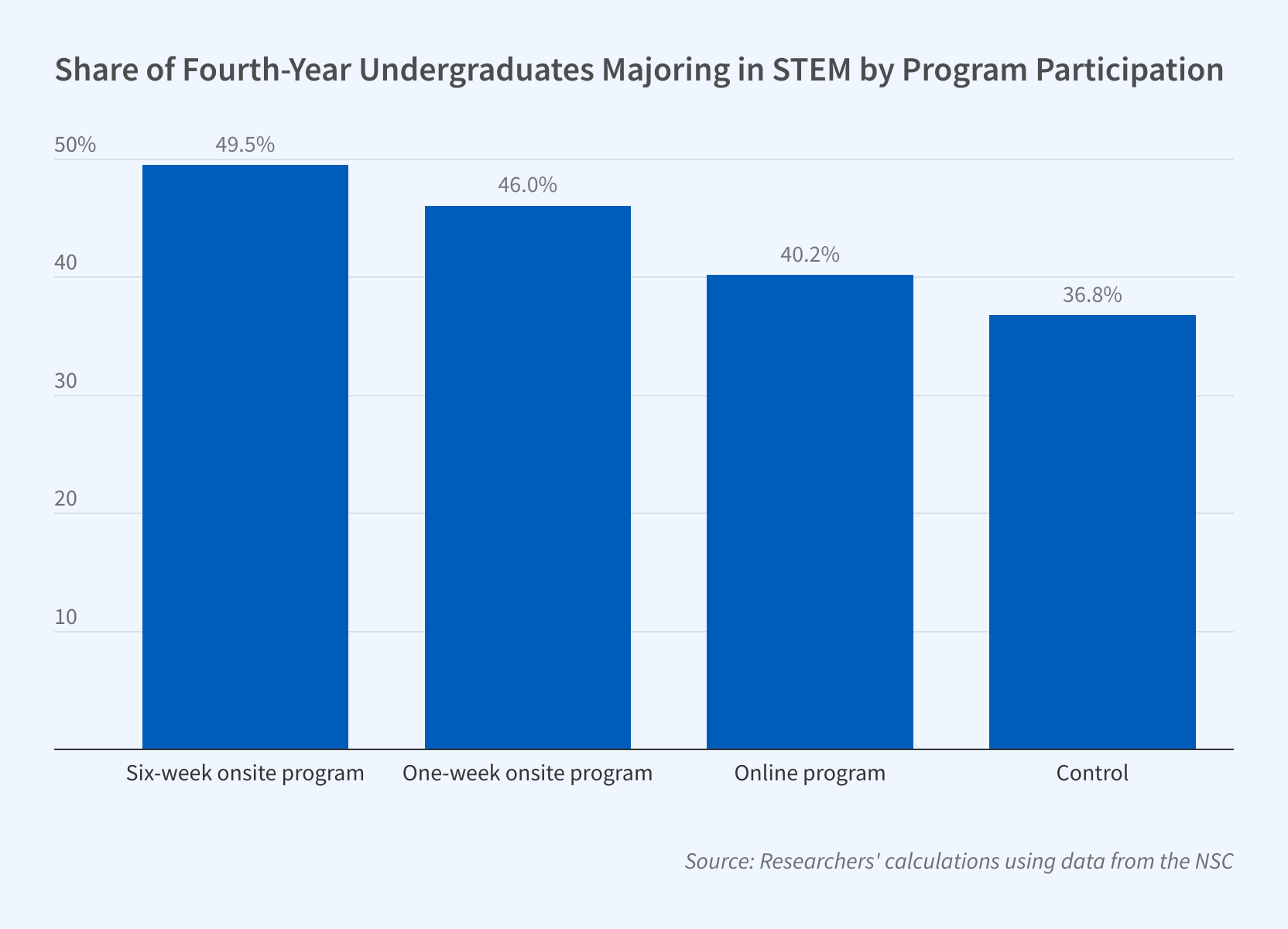

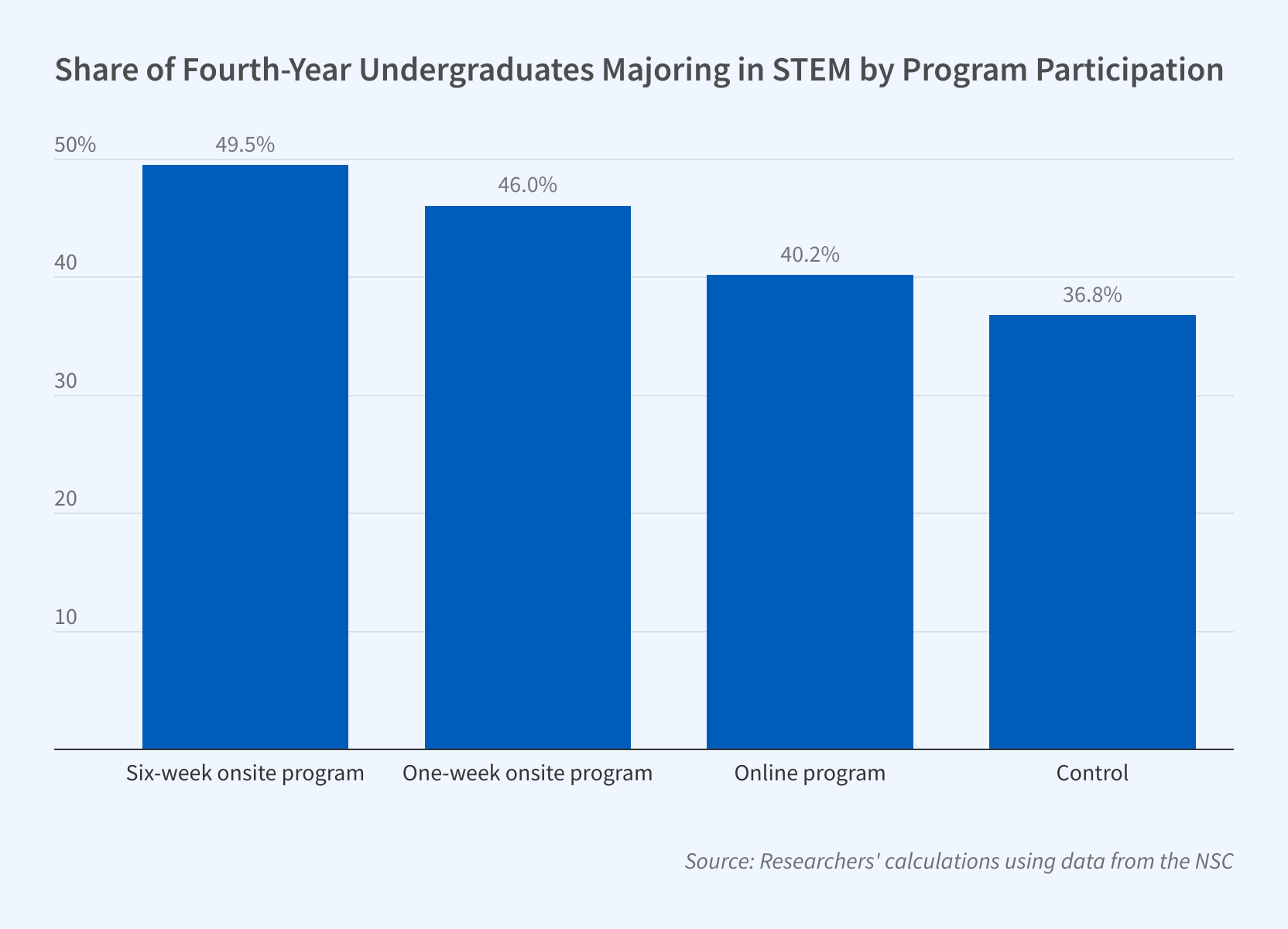

The STEM programs also increased on-time college graduation. Only 53 percent of students in the control group graduated within four years from any four-year school, despite being an academically talented group. For those who were randomly chosen to attend the six- or one-week STEM programs, the graduation rate was 8 percentage points higher. For the online program, it was 1.6 percentage points higher. In the control group, 34 percent of students graduated within four years with a STEM degree — 64 percent of degree recipients. The six-week program increased the rate at which students graduated with a STEM degree to 50.7 percent. The corresponding percentages were 46.8 percent for the one-week program and 37.2 percent for the online program. Most of these effects could be attributed to shifts in the quality of the institutions that graduates of the STEM summer programs, versus the control group, chose to attend. — Lauri Scherer

|

No comments:

Post a Comment