Hours worked declined for parents without college degrees but not for those with them, and childcare duties fell more heavily on mothers.

Two new studies show that school closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic significantly reduced parents' labor market activity. They reach different conclusions about which demographic groups were most affected, one concluding that it was parents without college degrees, the other pointing to mothers with school-aged children. These disparities may be the result of the studies' analysis of somewhat different time periods and geographic areas.

In The Impact of School and Childcare Closures on Labor Market Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic (NBER Working Paper 29641), Kairon Shayne D. Garcia and Benjamin W. Cowan report that parents, especially those without college degrees, responded to school closures by reducing their hours or shifting from full- to part-time work. They concentrate on the period from August 2020 to April 2021 because it covers the height of the pandemic and the first full academic term for which many schools switched to remote learning. Their study draws on cellphone data of foot traffic to pinpoint school closures, and on the Basic Monthly Current Population Survey for labor-supply information.

School closures were associated with a 3.8 percentage point decline in full-time work by mothers and a 2.5 percentage point decline by fathers, with the reductions primarily resulting from transitions to part-time work. Mothers on average worked 1.3 fewer hours a week and fathers 1.5 fewer hours. Parents without a college degree worked about two hours less per week, while those with college degrees showed negligible declines. Some studies of the early months of the pandemic — prior to the period considered in this study — found larger reductions in labor supply for mothers than for fathers, possibly because as the pandemic evolved, fathers pitched in more. Among unmarried parents, women were more likely than men to shift to part-time work; reductions in hours worked were comparable across genders. School closings were not associated with changes in labor supply among those who were not parents. The researchers explain the disparities across education groups by suggesting that more-educated workers were more likely to shift to working from home and to have access to alternative childcare arrangements or private schooling.

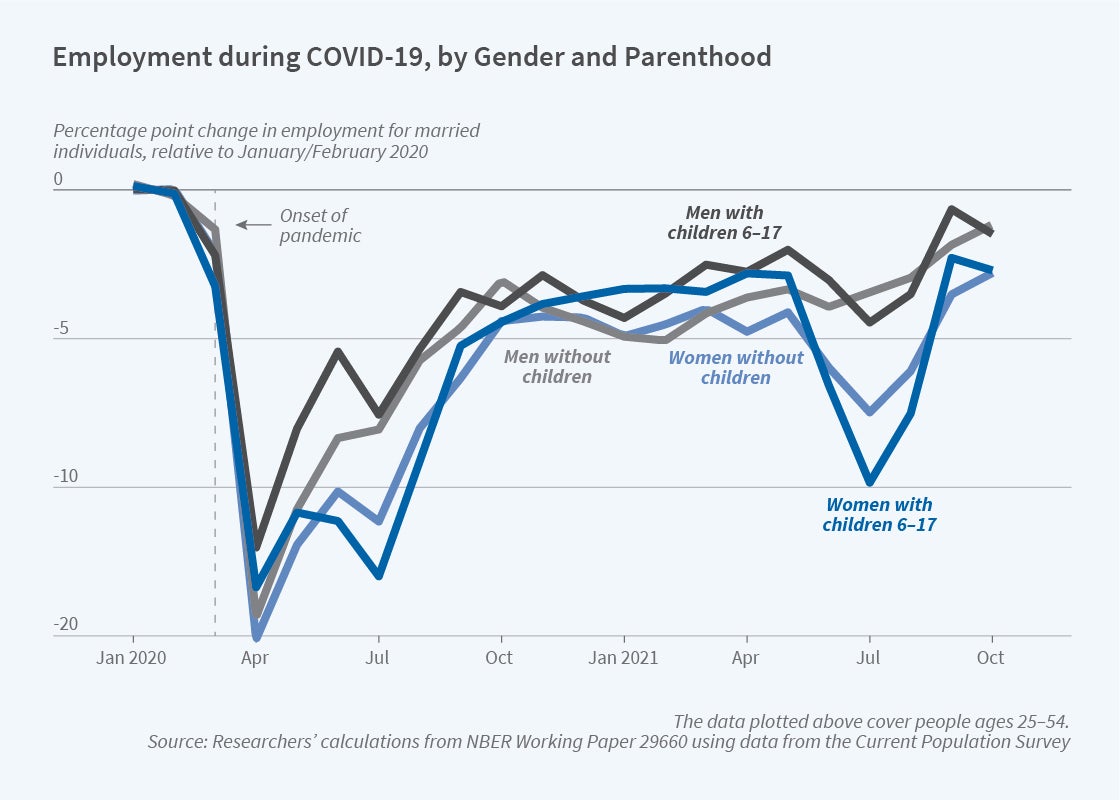

While Garcia and Cowan study changes in labor supply when schools close, Benjamin Hansen, Joseph J. Sabia, and Jessamyn Schaller also consider changes when they reopen. In Schools, Job Flexibility, and Married Women's Labor Supply: Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic (NBER Working Paper 29660), which also analyzes data from the Current Population Survey, they cover a broader time frame, September 2019 to October 2021. Their study spans all three academic years that were affected by the pandemic. It also includes a somewhat larger geographic area, with more rural locations, than the other study. The results suggest that in-person K-12 schooling was associated with employment gains for married women with school-aged children, but not for any other group, including single mothers and married custodial fathers.

After schools reopened, married women with school-aged children reported a 3.3 percentage point increase in employment and a 3.3 percentage point decline in remote work. The figures exclude women who were employed in the K-12 educational sector.

Mothers with and without college degrees showed comparable employment gains after schools reopened. Educational attainment, however, was a significant factor in work patterns. Mothers who completed college reduced remote work by 4.4 percentage points, versus a statistically insignificant 1.4 percentage point decline for those with less education.

The age of children made a difference. Mothers of children aged 12 to 17 saw a 3.9 percentage point increase in employment, compared with 2.5 percentage points for those with children aged 6 to 11. The decline in remote work was almost entirely among the mothers of the younger children. The researchers suggest that mothers with younger children may seek out jobs with greater flexibility, and that those with older children may have decided to leave the labor force when schools went remote in order to make sure that students kept up their grades.

— Steve Maas

Explaining the Decline of the US' Net Foreign Asset Position

Since the Great Recession, Americans have earned only moderate returns on their foreign investments while foreigners have reaped a bonanza on the boom in US stocks.

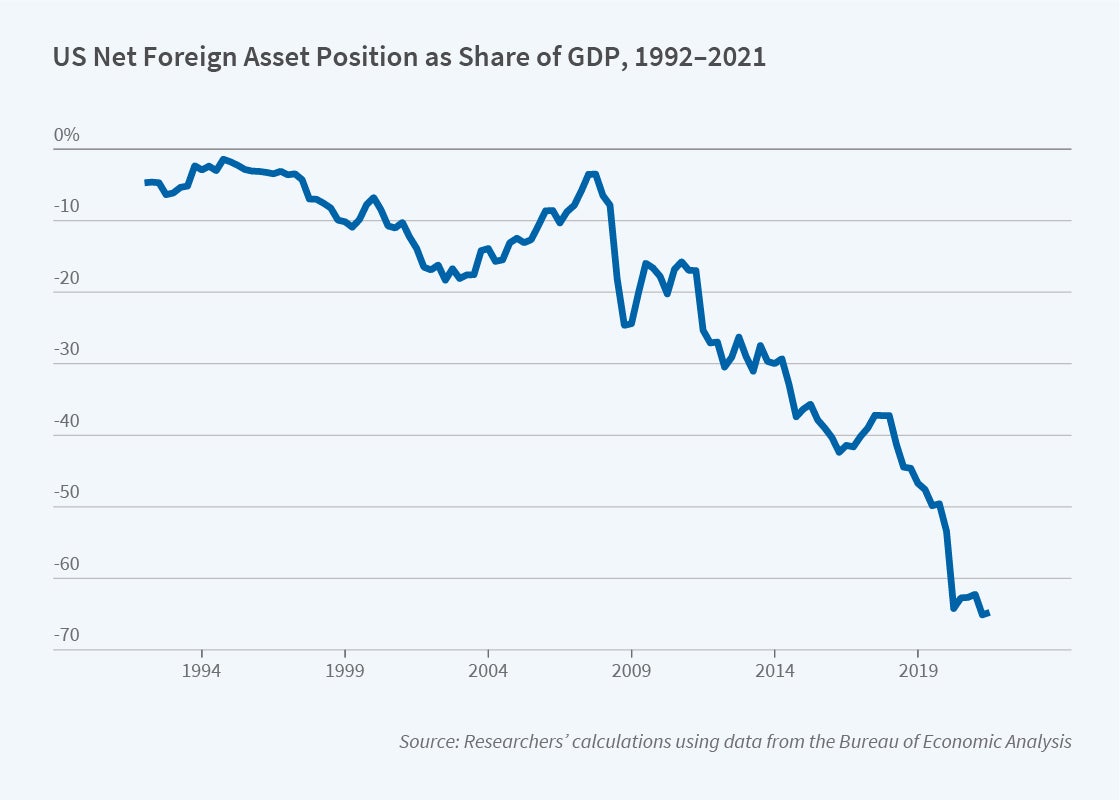

For decades, the United States appeared to enjoy a special privilege: although it imported more goods and services than it exported, its net foreign asset (NFA) position remained only slightly negative. Since the Great Recession, that privilege has disappeared and the NFA position — the difference between the foreign assets held by Americans and the US assets owned by foreigners — has declined sharply, even when measured as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP).

In The End of Privilege: A Reexamination of the Net Foreign Asset Position of the United States (NBER Working Paper 29771), Andrew Atkeson, Jonathan Heathcote, and Fabrizio Perri analyze why the NFA has deteriorated so much. They find that most of the change can be explained by a boom in US equity values that was not matched by foreign stock prices. Their paper upends the conventional explanation for America's so-called special privilege, which for a time allowed the United States to fund its large trade deficit with its earnings on foreign assets.

In the early years of this millennium, the most common explanation for the US' small NFA position was that Americans owned high-return foreign equities while foreigners held low-return US assets such as Treasury bonds. Data available at the time supported that view. By analyzing newer federal data, however, more finely tuned to capturing economic and financial flows and balance sheet positions, the researchers uncover a different explanation. They find that the relative performance of foreign and US holdings within asset classes, rather than differences in the type of assets held, accounts for most of the changes in the US NFA position between 2010 and 2021.

The researchers divide the dynamics of the US NFA position into three phases. In the first, from 1992 to 2002, the US NFA position deteriorated from minus 5 to minus 18 percent of GDP, paralleling rising deficits in the current account. During the second phase, from 2002 to 2010, the NFA position was roughly stable while the current account continued its negative trend. This was the era of America's special privilege, as previous researchers dubbed it, because it appeared that the US could finance its trade deficits with the high returns earned on foreign assets. That privilege came to an end in the third phase, 2010–21, when the NFA position fell by more than 40 percent even though the current account as a percentage of GDP was roughly stable. By 2021, the decline in the US NFA position had not only negated the phase of special privilege, but had fallen to a lower level than would be indicated by the cumulated current account deficits over the full period from 1992&nda sh;2021.

The reason for the plunge during the third phase was a boom in US stock prices that was not matched elsewhere. While Americans were earning moderate returns on their foreign stocks and other financial investments, foreigners were earning very high returns on their US holdings.

The researchers consider two possible explanations for the stronger returns on US stocks than their global counterparts during the last decade. One is that US firms made substantial investments in productive capital that are not measured in the national accounts, while the other is that they experienced a rise in market power and a corresponding increase in monopoly profits. If the first explanation was correct, the US would have experienced a period of low or negative measured output and a huge trade and current account deficit, far beyond the deficit actually reported. The researchers conclude that since this was not observed, unmeasured investments may have contributed to the decline of the NFA position, but they are unlikely to be a dominant factor. A rise in monopoly profits and a larger share of value added accruing to the owners of firms, however, appears much more consistent with the NFA movement and other macroeconomic data. Since foreign investors own roughly 30 percent of the US corporate sector, their share of the increased profitability of this sector corresponds to an annual flow of about 1.3 percent of US GDP.

— Laurent Belsie

Enclosure of Rural England Boosted Productivity and Inequality

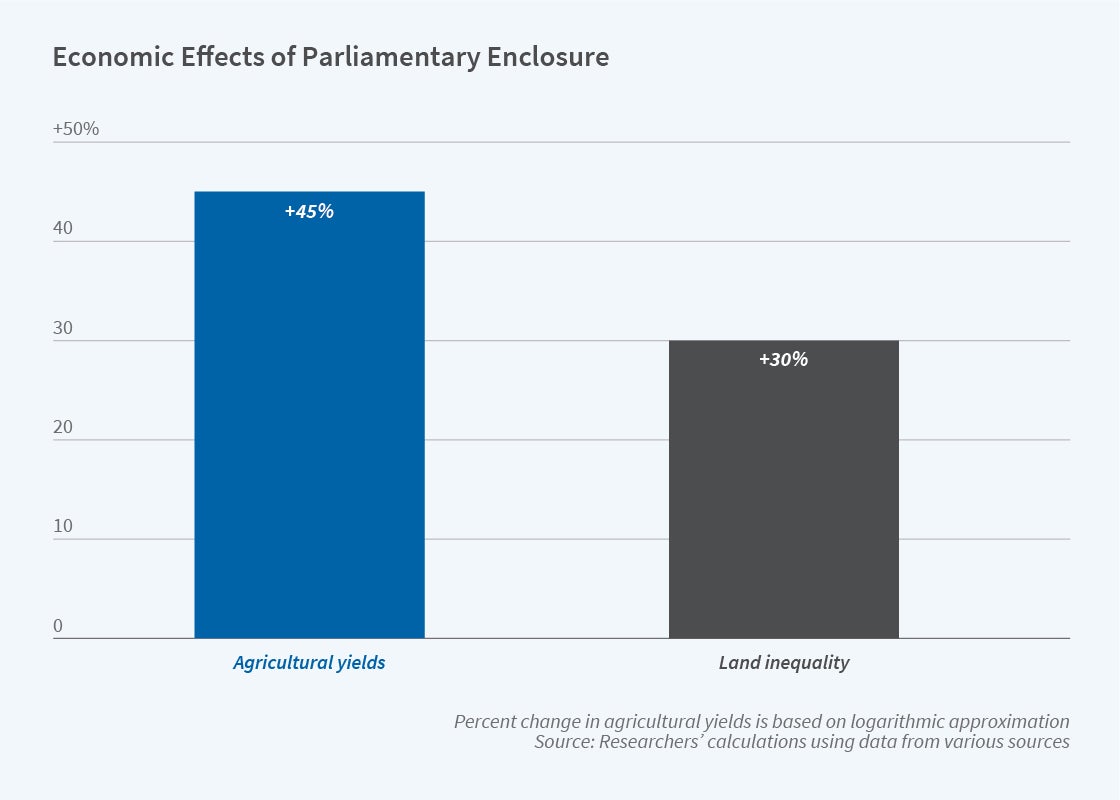

Parliamentary enclosures increased agricultural yields as well as inequality in the distribution of landholdings in enclosing parishes.

Enclosure involved privatizing rural land in England that had been in common ownership and consolidating scattered plots that had been farmed by individual households. The process began in the Middle Ages, and originally took place only when there was unanimous local agreement. At the beginning of the 18th century, large parts of the country had not been enclosed.

Around 1700, Parliament allowed owners of three-quarters of the land in an area, by value, to petition for an act of enclosure of all common property. This institutionalized a process for proceeding with enclosure over the opposition of some affected residents. By about 1900, virtually all of England was under private, consolidated ownership.

In The Economic Effects of the English Parliamentary Enclosures (NBER Working Paper 29772), Leander Heldring, James A. Robinson, and Sebastian Vollmer study all English Parliamentary enclosure acts between 1750 and 1830 and describe their impact. The researchers assemble data on agrarian outcomes in over 15,000 parishes, and they compare parishes that were enclosed in the Parliamentary period, 1750–1830, to those that were not enclosed by this method at the end of the period. Because the decision to file an enclosure petition likely correlated with parish attributes, the researchers develop an estimation strategy that draws on information on the success or failure of enclosure petitions for nearby parishes.

The analysis finds that by 1830, enclosures were associated, on average, with a 45 percent increase in agricultural yields. Inequality in land ownership, measured by the value of land held by different owners, also increased following enclosure. The researchers also estimate that the Gini coefficient, a common measure of income or wealth inequality, rose by 30 percent in parishes that enclosed relative to those that did not. These results are in line with theoretical arguments pointing to potential inefficiencies in shared governance and ownership of land. Even in communities as small, cohesive, and stable as a parish, informal governance mechanisms coordinating behavior and investment appear to have been less efficient than those of private ownership.

Contemporary advocates of Parliamentary enclosure suggested that it promoted investment, innovation, and experimentation in new techniques. The researchers explore the claim regarding innovation by examining the number of agricultural patents filed in a parish, which increased modestly following enclosure. The quality of local infrastructure, measured by the probability that surveyors rated a road in the parish to be of poor quality, also improved. The share of acreage in a parish that was either sown with turnips or subject to appropriate fallowing practices — ways to replenish depleted soils and improve output — also rose following enclosure. Prior to enclosure, the practices may not have been adopted because their implementation required coordination among villagers with disparate interests in commonly governed fields. Parliamentary enclosure gave everyone the freedom to implement best practices without the need for coordination.

— Lauri Scherer

No comments:

Post a Comment